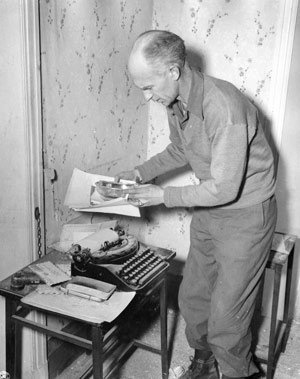

Being under fire on the beachhead at Anzio was not pleasant, Pyle wrote.

WITH THE ALLIED BEACHHEAD FORCES IN ITALY, March 28, 1944 – When you get to Anzio you waste no time getting off the boat, for you have been feeling pretty much like a clay pigeon in a shooting gallery. But after a few hours in Anzio you wish you were back on the boat, for you could hardly describe being ashore as any haven of peacefulness.

As we came into the harbor, shells skipped the water within a hundred yards of us.

In our first day ashore, a bomb exploded so close to the place where I was sitting that it almost knocked us down with fright. It smacked into the trees a short distance away.

And on the third day ashore, an 88 went off within twenty yards of us.

I wished I was in New York.

*

When I write about my own occasional association with shells and bombs, there is one thing I want you folks at home to be sure to get straight. And that is that the other correspondents are in the same boat – many of them much more so. You know about my own small experiences, because it’s my job to write about how these things sound and feel. But you don’t know what the other reporters go through, because it usually isn’t their job to write about themselves.

There are correspondents here on the beachhead, and on the Cassino front also, who have had dozens of close shaves. I know of one correspondent who was knocked down four times by near misses on his first day here.

Two correspondents, Reynolds Packer of the United Press and Homer Bigart of the New York Herald-Tribune, have been on the beachhead since D-day without a moment’s respite. They’ve become so veteran that they don’t even mention a shell striking twenty yards away.

*

On this beachhead every inch of our territory is under German artillery fire. There is no rear area that is immune, as in most battle zones. They can reach us with their 88’s, and they use everything from that on up.

I don’t mean to suggest that they keep every foot of our territory drenched with shells all the time, for they certainly don’t. They are short of ammunition, for one thing. But they can reach us, and you never know where they’ll shoot next. You’re just as liable to get hit standing in the doorway of the villa where you sleep at night, as you are in a command post five miles out in the field.

Some days they shell us hard, and some days hours will go by without a single shell coming over. Yet nobody is wholly safe, and anybody who says he has been around Anzio two days without ever having a shell hit within a hundred yards of him is just bragging.

*

People who know the sounds of warfare intimately are puzzled and irritated by the sounds up here. For some reason, you can’t tell anything about anything.

The Germans shoot shells of half a dozen sizes, each of which makes a different sound of explosion. You can’t gauge distance at all. One shell may land within your block and sound not much louder than a shotgun. Another landing a quarter mile away makes the earth tremble as in an earthquake, and starts your heart to pounding.

You can’t gauge direction, either. The 88 that hit within twenty yards of us didn’t make so much noise. I would have sworn it was two hundred yards away and in the opposite direction.

Sometimes you hear them coming, and sometimes you don’t. Sometimes you hear the shell whine after you’ve heard it explode. Sometimes you hear it whine and it never explodes. Sometimes the house trembles and shakes and you hear no explosion at all.

But I’ve found out one thing here that’s just the same as anywhere else – and that’s that old weakness in the joints when they get to landing close. I’ve been weak all over Tunisia and Sicily, and in parts of Italy, and I get weaker than ever up here.

When the German raiders come over at night, and the sky lights up bright as day with flares, and ack-ack guns set up a turmoil and pretty soon you hear and feel that terrible power of exploding bombs – well, your elbows get flabby and you breathe in little short jerks, and your chest feels empty, and you’re too excited to do anything but hope.