Nearly a year before the U.S. entered the war, Pyle describes the awe he felt as he watched the German air attacks on London.

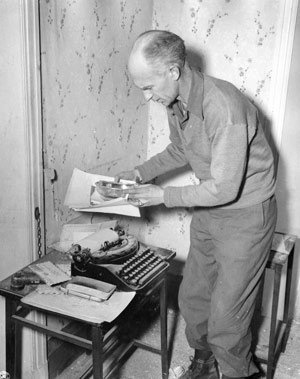

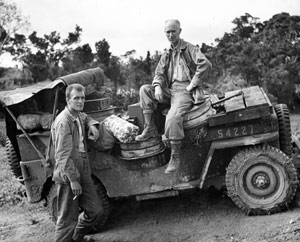

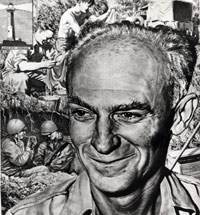

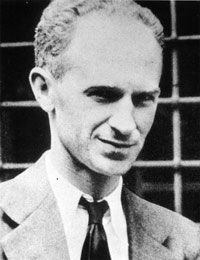

For many journalists, Ernest Taylor Pyle, an Indiana native better known as "Ernie," continues to be an icon of excellence decades after his death at the hands of a Japanese machine-gunner in World War II. For the last 10 years of his life, he wrote feature columns six times a week, primarily for Scripps-Howard newspapers. As his fame increased during the war, other newspapers, including weekly ones, published Pyle’s work.

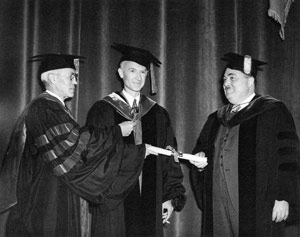

In 1944 Ernie Pyle won a Pulitzer Prize for his stories about the ordinary soldiers fighting in World War II.

On these pages is a selection of his wartime columns in both written and spoken versions. We welcome your comments about the site and stories you might have to tell about meeting Pyle or reading Pyle’s columns.

These columns are reprinted with the permission of the Scripps Howard Foundation.

Nearly a year before the U.S. entered the war, Pyle describes the awe he felt as he watched the German air attacks on London.

In this column, Pyle explains how servicemen going into battle will be changed by the experience.

In this column, Pyle writes knowingly about a pilot he spent several years with before the war as an aviation correspondent.

This is the first of several columns that Pyle wrote about a tank battle – this one telling the story of a U.S. defeat.

This is the kind of column that endeared Pyle to the troops – a column about soldiers digging ditches and grousing about folks back home.

This is one of several columns that Pyle wrote about the medical corps.

This column shows how the war has turned soldiers, especially those in the First Infantry Division, into hard-nosed fighters and killers.

From one of Ernie Pyle’s most famous columns, these words celebrate foot soldiers.

Winning a battle and capturing enemy soldiers boosts morale, according to the final North African column in this series.

Pyle chronicles the Allied invasion of Sicily, which was a lot easier than the Normandy landing would be a year later.

Mapping and Engineering the War

This is one of several columns that Pyle wrote about the soldiers who kept the Army going.

When Pyle took a break from the war in late summer 1943 and came back to the U.S. for a while, he had mixed feelings.

This is the most famous and most widely-reprinted column by Ernie Pyle.

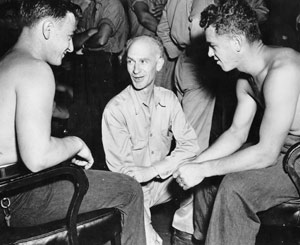

Members of the Armed Forces admired cartoonist Bill Mauldin just about as much as they admired the writing of Ernie Pyle.

Life for airmen might have been easier, Pyle wrote, but they and Pyle’s beloved infantry were both necessary to win the war.

Excerpts from two letters Pyle wrote in late winter and early spring of 1944 to friends and relations back home.

Buck Eversole: One of the Great Men of the War

Ernie Pyle wrote several columns about Eversole who was one of Pyle’s favorite soldiers in the war.

Being under fire on the beachhead at Anzio was not pleasant, Pyle wrote.

Pyle didn’t make many references to Black troops, but he did in this story about the people who provided food, clothing and ammunition.

In the first of three D-Day columns included in this series, Pyle marvels at and celebrates the Allied successes.

In the second of three D-Day columns in this series, Pyle sees the terrible cost of victory on the Normandy beaches.

A Long Thin Line of Personal Anguish

In the third and final of the three D-Day columns in this series, Pyle personalizes the losses on the beaches of Normandy.

Once in a while, Pyle told funny stories.

The quiet heroism of the troops getting ready for battle impressed Pyle.

From time to time Pyle turned his attention from the infantry to the units that helped supply or support the infantry.

Pyle marveled at the men who fixed things that were broken.

The tactics that helped the Allies beat the Germans are described by Pyle in this column.

Pyle finds joy as the Allied troops capture Paris.

Nearly a year before the U.S. entered the war, Pyle describes the awe he felt as he watched the German air attacks on London.

Nearly a year before the U.S. entered the war, Pyle describes the awe he felt as he watched the German air attacks on London.

One of the things that endeared Pyle to his readers was the way in which he made his family part of their lives.

In writing about his writing, Pyle showed elements of both ego and modesty.

Pyle writes about the “The Story of GI Joe,” a movie based on Pyle’s columns.

A Finger on the Wide Web of the War

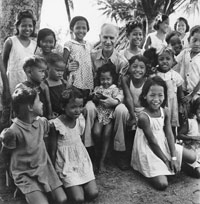

Pyle describes the U.S. forces in the Mariana Islands.

Reflecting the biases of his times, Pyle found the Japanese soldiers less than human.

Pyle describes what it’s like to return from a bombing run.

Pyle writes about life on an aircraft carrier.

This column was never completed. A draft of it was found in Pyle’s pocket, April 18, 1945, the day he was killed.

This column, published posthumously, describes Pyle’s first direct contact with Japanese soldiers.

In his last published column, which was issued posthumously, Pyle honors the memory of a fellow war correspondent.